Glasgow Airport meets Metafiction

Margaret Atwood's 'The Blind Assassin' - Winner of the 2000 Booker Prize

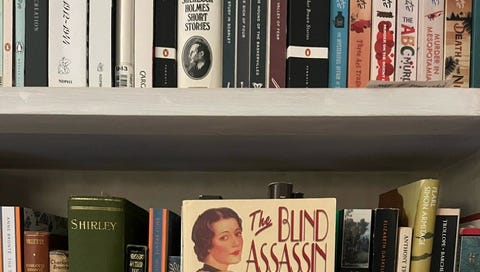

I started The Blind Assassin recently in Glasgow airport on a layover between London and Outer Hebridean island, Barra (mistake). It was my next Booker prize read, courtesy of a nice World of Books order. Margaret Atwood immediately commands your attention (the first line is ‘Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off the bridge’ – at once informative and ambiguous). The novel follows Iris Chase, our narrator’s story as she sits down to write her memoirs. The narrative flips between Iris now (older and dependent on a woman called Myra for care), Iris’ narrative of her girlhood, newspaper articles and the book within a book, the ‘Blind Assassin’. Oh and also the book within a book within a book, told by the initially nameless man in the ‘Blind Assassin’. However, it was fairly ambitious of me to embark on all of these fictional dimensions in a place as over-stimulating as Glasgow airport, but once on Barra I had a bit more headspace.

I haven’t quite worked out how good an idea it is to try and summarise the plot in these essays. It always feels fairly futile, especially for a book of this length, but it does seem rude not to. So – Iris and her younger sister Laura lose their mother at a young age, and essentially run rampant in their big house in Port Ticonderoga, south of Ontario. They only have an increasingly alcoholic father and a benevolent, opinionated, yet slightly passive nanny, Reenie, to care for them. Iris is often charged with watching out for the more impetuous and insubordinate Laura, which comes to define most of their lives. However, just as you settle into this traditional memoir-style narrative, it is interrupted by the beginning of another book, the eponymous ‘Blind Assassin’ (quotation marks to help you (but mainly me) work out whether I’m talking about the book or the book within a book). This tells of a woman and her lover who, during their trysts in various dives and ‘borrowed’ flats, tells her a science-fiction story set in a civilisation called Sakiel-Norn. The ‘Blind Assassin’ is supposedly written by Laura, and published by Iris, but the true genesis of the book within the book turns out to be more complex.

The switching between writers and times is masterfully managed. Coincidentally I am currently reading David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction which is making me think a lot more about Atwood’s construction of prose, especially the ways in which she plays with voice, authorship and time. Lodge argues that ‘through time-shift, narrative avoids presenting life as just one damn thing after another, and allows us to make connections of causality and irony between widely separated events’. The Blind Assassin has great examples of this – the reader sees patterns of Laura’s behaviour throughout her life (curiosity, throwing herself off things) and patterns of male domination over the two sisters. Alongside these ‘time-shifts’, Atwood also presents two very different narrative styles. She perfectly balances the voice of the ageing Iris, who is writing her story out of a sort of desperation to be heard finally, and the more daring narrative of the interspersed chapters of the ‘Blind Assassin’. The fear of the elder Iris is reflected back cruelly by the youthful physicality of the more intimate scenes of the book within a book. Iris has now been abandoned by her remaining family and friends, all except Myra, who is revealed to be Iris’ old nanny’s daughter. These two figures, Reenie and Myra, act as another perspective in the novel, always commenting and at times becoming spokeswomen for the outsiders’ opinions. It may sound confusing, but I assure you that is my fault rather than Atwood’s. She develops all of these voices and times in such a way that the novel becomes all-encompassing, and certainly worlds away from Lodge’s ‘one damn thing after another’.

Although I’ve read a few books in between The Blind Assassin and Troubles, I found myself noticing some similarities. And as always, it is where these similarities end that it gets interesting. Namely, both incorporate local news articles and reports. But where J.G. Farrell uses these to report on a wider political situation in Ireland, Atwood uses these articles to provide an ‘objective’ perspective on events. They report on the death of Iris’ sister, on speeches made by Richard (the man she is married off to very young) and on parties, all indirectly involving Iris and yet not mentioning her at all. It is a clever way of showing the reader quite how severely Iris’ life has been dominated by other people and works completely differently to Farrell’s peritexts. They offer a sort of explanation for why Iris yearns to tell her side of the story now.

I certainly felt the length of the book. At 600-ish pages, it’s a tome, which I did enjoy but felt latterly that it dragged a little. I read a review that said that the revelations which come at the very end of the book would have been useful to have at the beginning, which is a fundamentally stupid thing to think, let alone publish, but I do sort of see the point. The secrets about the family are revealed at the very end of the book, and they almost seem like an afterthought. After so much detailed and carefully engineered narrative, the ‘explanation’ of Laura and Richard’s demises fall a little flat. But that is my only complaint – I loved it.

I also found it heart-achingly sad. The older Iris describes in painful detail her trips to a specific café to get a doughnut and coffee (despite the doctor’s warnings about caffeine) so that she can go to the toilet cubicle and read Laura’s graffiti. The trips are increasingly scary and hazardous given Iris’ decreasing health, and this particular image makes me want to weep.

At the end of each of these essays, I find myself beating myself up about the parts I haven’t included. I haven’t written about the insight into Canada during the First or Second World War, or the important role that the sisters’ old house plays in their lives. Or lots of things really, but I am coming to learn that I will write about only what I find most interesting, in the hope that someone also does. So, this concludes my non-exhaustive, yet somehow exhaustingly complicated essay about The Blind Assassin.

Intelligent as ever - I only wish you knew how well you write. Although perhaps the self-deprecating moments are just a clever additional layer of metafiction. A great essay with what sounds like a mammoth subject